In China, coal is king. The source of about 70 percent of the nation's energy supply, it has long been the engine of the Chinese economy. But the reign of coal, which has the highest carbon content of all fossil fuels, has resulted in unintended consequences, from local air pollution to global climate change. While China is currently moving ahead with a national carbon market covering large emitters, an ongoing question remains whether and how the country might also directly restrict the use of coal to tackle the triple threat of air pollution, climate change and energy insecurity. One option under discussion involves imposing limits on the use of coal or on all fossil fuels (coal, oil and natural gas) at the national or regional levels.

Now a new study by researchers at the MIT Joint Program on the Policy of Global Change, Tsinghua University, and ETH Zurich examines this option in detail. Appearing in the May 2016 issue of Energy Economics, the study compares the economic impacts of imposing coal, energy and carbon caps at regional and national levels.

Using the China Regional Energy Model (C-REM), a multi-commodity, multi-regional computable general equilibrium model of the Chinese economy that represents 30 of its provinces, the researchers found that a cap on coal only would cost about twice as much as a cap on all fossil fuels while cutting fossil energy use to the same level, and exact economic hardship on regions where demand for coal is high and availability of low-carbon substitutes is low. For the same level of carbon reduction, a coal cap would impose a much higher and more concentrated economic impact.

According to the study, the most cost-effective energy cap policy would be to combine a cap on "downstream" fossil fuel use (processing and consumption by manufacturers and consumers) with a national energy saving allowance trading system among provinces. This system closely approximates a cap on carbon because coal, which is reduced most cost-effectively by an energy cap, also has the highest carbon content among the fuels targeted. Under the fossil energy cap-and-trade policy envisioned by the study, provinces where energy savings costs are higher could use more fossil energy by buying permits from other provinces where those costs are lower.

"A cap on all fossil fuels rather than on coal alone, along with a cross-provincial energy saving allowance trading system would not only give China more flexibility in how it reduces CO2 emissions but also avoid significant economic impacts in those regions that depend heavily on coal," says Da Zhang, a Joint Program postdoctoral associate who co-authored the study with Sloan School of Management Assistant Professor Valerie Karplus (who has directed the MIT-Tsinghua China Energy and Climate Project (CECP) for the Joint Program) and ETH Zurich Assistant Professor Sebastian Rausch.

Interestingly, the researchers also found this approach nearly as effective in reducing CO2 emissions as a national CO2 emissions trading system that puts a price on fossil energy use based on its carbon content, because both policy designs will result in similar coal-use reduction patterns across provinces. Since it would be easier to implement, an energy cap could serve as a steppingstone to a robust CO2 emissions trading system.

Since the study concluded, China ultimately decided to pursue a national CO2 emissions trading scheme starting in 2017. The study suggests the merits of this choice, which performs better than all energy cap designs considered.

"Our study compares the economic performance of a menu of potential policy designs, and it shows the value of China's decision to focus on controlling carbon emissions through a cap-and-trade system, especially compared to a system that only constrains coal use, missing other carbon-intensive fuels and exacting sharp and concentrated regional economic impacts," says Karplus.

The study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China through the Institute for Energy, Environment and Economy at Tsinghua University; the Social Science Key Research Program of the National Social Science Foundation of China; Rio Tinto China; and the founding sponsors of the China Energy and Climate Project in the MIT Joint Program: Eni, the French Development Agency, ICF International and Shell.

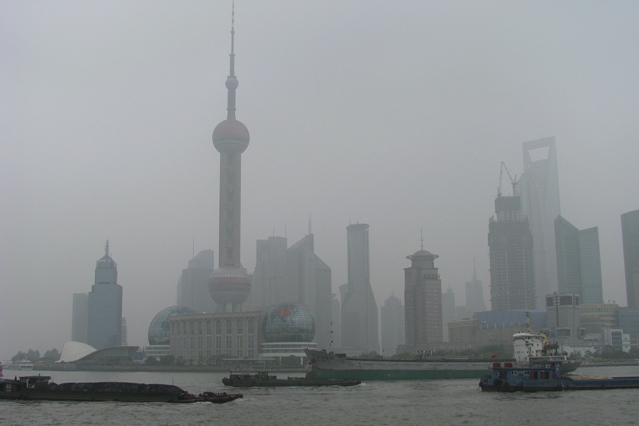

Photo: Coal barges head upstream on the Huangpu River in Shanghai (Source: Peter Dowley)